It seems we have an imposter among us! Or at least many people claim to feel like an imposter.

Imposter syndrome is a psychological occurrence in which an individual doubts their competency and fears that this could make them an ‘imposter’ that others could discover. This idea is from a 1978 paper by two psychologists, who argued that high achieving women are especially prone to this sort of insecurity despite their high achievements. It is typically discussed in the context of women and ethnic minorities in academia.

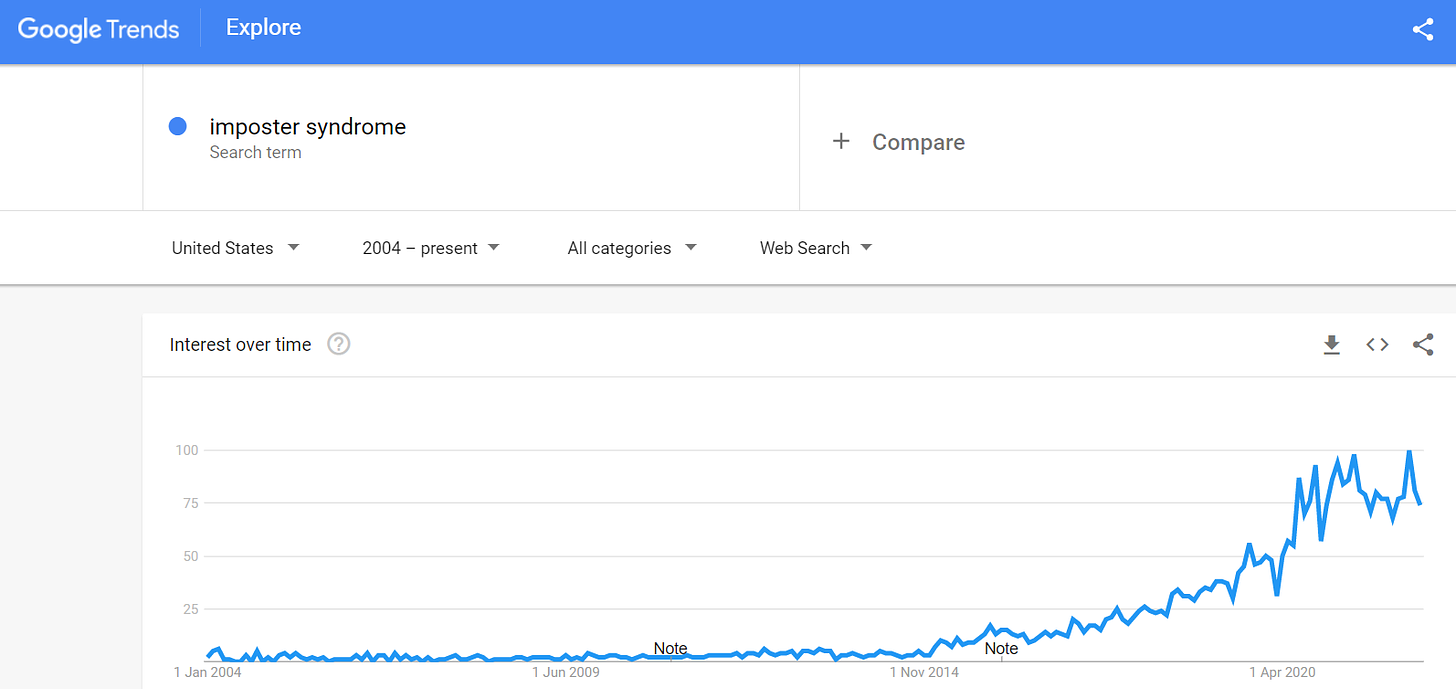

The popularity of the term imposter syndrome has been rapidly rising in recent years. Suggesting that imposter syndrome might be spreading, or at least people have had a large level of occupational insecurity which they have only just found a word to define. So it’s important we ask, what is causing so many people to feel like imposters?

To me the best explanation for Imposter syndrome is the most obvious one, some people really are imposters. If someone says they are worried about being incompetent then maybe they are, after all, people are generally rational. If in a survey you ask people if they are overweight and some say yes, your first response should not be to assume they have body dysmorphia or an eating disorder. Your first response should be to believe them. We have concepts such as dysmorphia precisely to describe unusual perception inaccuracies - exceptions that prove the rule that people are somewhat self-aware and perceptive.

Contrary to the popular ‘Dunning-Kruger effect’ people are quite accurate in estimating their ability. Their estimates of percentile on intelligence tests are linearly related to their actual centile and correlate well (r = 0.54).

I could only find a few studies with data to test this hypothesis that low ability relative to your colleagues can cause imposter syndrome. This study tracked 818 college students to look for what triggered the syndrome. The focus of the study was on studying the effects of first-generation college status and perception of competition. They use multi-level modelling to argue that there are interaction effects between first-generation status and classroom competition.

Their most illuminating results were the simplest (as is usually the case) - the correlation matrix of their variables. Exactly in line with the theory that imposter syndrome is caused by incompetence, they find low course grades, low attendance, low course engagement (lack of curiosity) and classroom competition (the perception of others working harder than you) predict feelings of being an imposter. People have imposter syndrome because they are incompetent people pretending to be something they are not - a good student.

But why doesn’t SAT and first-generation status (likely an indicator of hereditary low IQ) have much of an effect on imposter feelings? My guess is that people sort somewhat into courses of a difficulty level to match their abilities. A student with a strong SAT would do well in Psychology but may feel like an imposter if he did Maths.

As for the supposed interaction between first-generation status and perceived competition my speculation is that this is caused by the FG status correlation with ability. If you are high ability and you perceive competition you step up to the plate. If you are lazy or have low ability then you don’t step up to the competition, leading to the realisation that you are the imposter. However, the authors suggest that it is caused by the

“cultural mismatch between the interdependent values that FG students bring to college and the individualistic or zero-sum values communicated by classroom competition”.

Although such cultural differences may exist, their relevance just doesn’t pass the sniff test. Wouldn’t the more competitive, individualistic, self-centred students be more likely to worry about being an imposter?

Despite the good evidence for imposter syndrome being caused by students actually being imposters, the study never once brings itself to mention why low grades are associated with feelings of being an imposter.

The second study looked at 491 undergraduates and proposed the below model and a couple of others. The effects on the left are for women and the effects on the right are for men. Notice the arrows - the proposed direction of causality. They think imposter syndrome causes a higher GPA. Yes, causality could work in this direction but the opposite does seem more natural. You can feel anxious about your work because you have high standards or because your work is poor. In their structural model, they find the imposter phenomenon itself is directly related to a slightly higher GPA but only in women. But in the model, feeling like an imposter reduces one’s ‘academic self-concept’ which is positively related to GPA. It’s not entirely clear to me that there is much difference between feeling like an imposter in academia and having a low ‘self-concept’ of oneself as an academic type. My guess is their model manages to separate the effects of having high standards and not being very good.

Academic disengagement also predicts a lower GPA. Overall this is not good evidence for or against the idea that feeling like an imposter is caused by being one.

‘Gender stigma consciousness’ is associated with imposter syndrome. But being left-wing is associated with mental illness, so I’m not sure we can interpret it the way the authors expect us to as an issue of ‘internalising stereotypes’, especially since ‘gender stigma consciousness’ has the same effect for men and women.

A third study uses a much smaller sample size of 127 students. Again they do not consider the possibility that low performance could cause imposter syndrome. This study find a positive correlation (r = 0.29, p < 0.05) between high school GPA and imposter syndrome! This directly contradicts our theory, right? Well not necessarily, the sample is of recruited students from Maths and Psychology! Maths is much harder at university and many will struggle or feel like imposters. Yet to get into maths you need a solid high school GPA. As we learnt from looking at the first study, what likely matters is your performance relative to your peers - these are the people imposters believe they are pretending to be.

Overall we have one large study that supports our hypothesis, a medium-sized study which doesn’t show much and a small flawed study that contradicts our hypothesis. Overall, I’d say our hypothesis is probably right

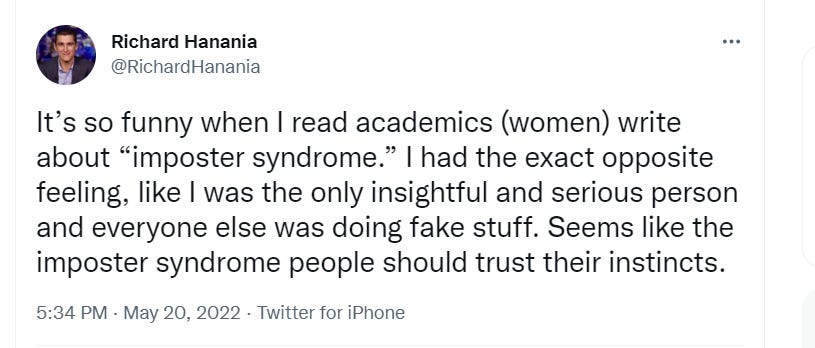

Denial or just failure to even consider our obvious explanation for imposter syndrome seems to be incredibly prevalent. I can’t find any study that provides a hypothesis for why low relative ability could cause imposter syndrome. In fact, the only time I have seen anyone else consider the obvious explanation was Richard Hanania in this tweet. Responses to the tweet were in denial and can be characterised by the internet jargon ‘seethe and cope’.

This denial seems to be extremely common. Many academics have actually distorted the meaning of imposter syndrome, defining it as insecurity regarding one's abilities despite being very successful. But they do not provide any evidence to prove that people with imposter syndrome are actually unjustified in their beliefs. In this essay for the Harvard Business Review, the authors just casually state that imposter syndrome ‘disproportionately affects high-achieving people, who find it difficult to accept their accomplishments’. But if anything the evidence points the other way. They give no justification, they provide a link to another blog that does not justify this statement and it flatly contradicts the statistical evidence.

This line of thoughtlessness appears to come from the original paper on Imposter Syndrome. The authors study the phenomena in high achieving women, claiming it is particularly prevalent amongst them. But that’s sample selection bias! The authors' sample is of female clients and academics in workshops they taught at university. It would be like studying intelligent poor people at university and then claiming that poor people are especially smart.

An analogy to this whole situation would be defining obesity as people who are substantially overweight, despite eating less than 2,500 calories a day. You can’t simply define an illness to exclude causes you do not want to think about.

So what on earth is going on? Why aren’t people studying the very likely and very obvious truth of imposter syndrome. Maybe this is just a case of people not wanting to admit that they are not as good as they want to be or expected to be. However, I suspect there’s an implicit political agenda to these denials.

You see the original study on imposter syndrome claimed women were more likely to suffer from it because they had internalised a stereotype of women being incompetent. Thus imposter syndrome was a sad symptom of the sexist nature of our culture. Thus the concept is politically useful. This is incredibly ironic on two fronts.

First, stereotypes are actually very accurate, there is a globally held stereotype that men are more competent than women and women really do worse in academia and worse in pay more generally. If there really were higher levels of imposter syndrome in women that would indicate that they are more likely to struggle in academia.

Secondly, it is far from clear that women are more likely to experience imposter syndrome. There was no correlation between gender and feelings of imposter syndrome in this study of 818 students nor do men and women differ in imposter feelings in the study of 491 students. However, in this study of only 127 students, the women do have higher levels of imposter syndrome. Nonetheless, I’d speculate that women are slightly more predisposed to imposter syndrome because they generally have higher levels of anxiety/neuroticism. It seems very likely that perfectionism (OCD), depression and other mental illnesses contribute to, or at least related to, imposter syndrome.

There’s also, apparently, an ethnic angle to imposter syndrome. Some studies claim and imply that imposter syndrome is a big issue for ethnic minorities. My personal favourite is the paper ‘Imposter Syndrome Threatens Diversity’. To show you just how prevalent this narrative is, let me quote from an op-ed by a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute:

“The website DiversityInc warns that imposter syndrome can “take a heavy toll on people of color, particularly African Americans.” A paper from the Center for Community Solutions examines “The devaluation of oneself: Dealing with imposter syndrome in the Black community.” A Maryville University paper explores “Imposter Syndrome from a Black Perspective.” A recent Harvard Business Review essay highlights the imposter syndrome problem particularly as it affects black women.”

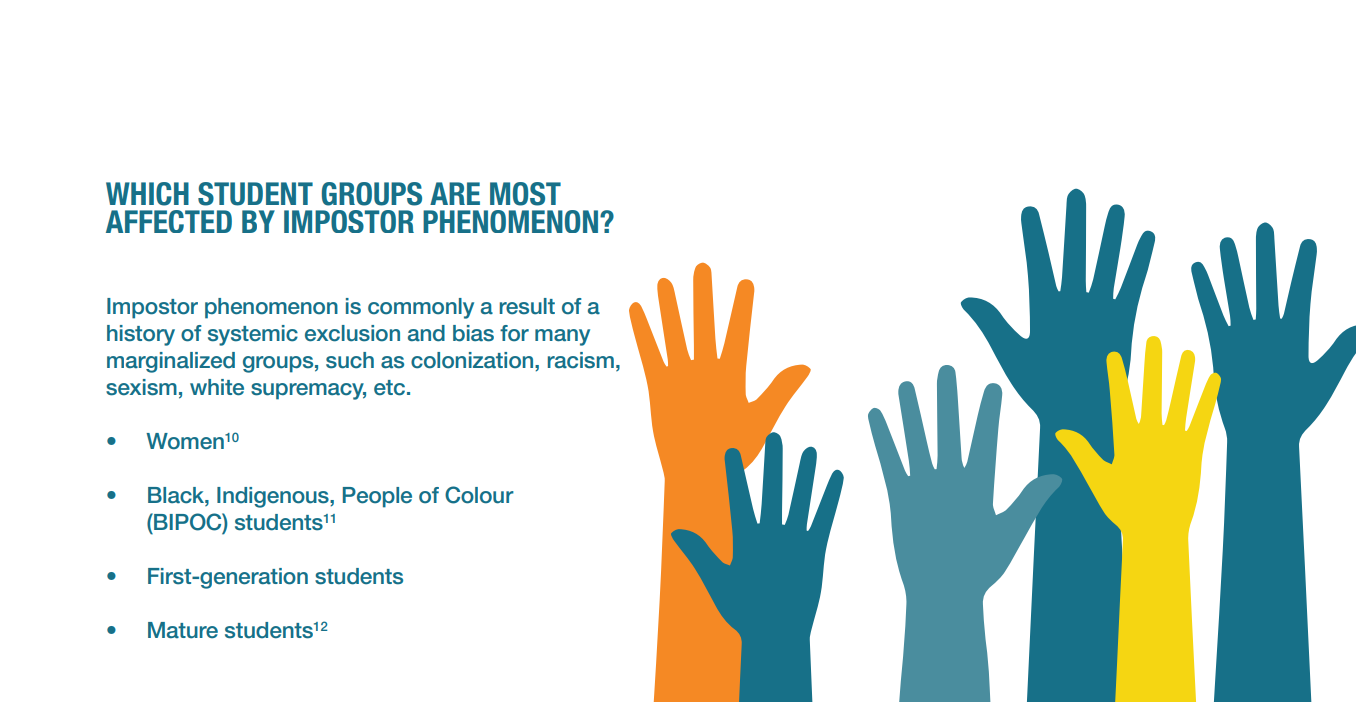

And yet despite all these studies and claims, I can’t find any evidence to suggest minorities are especially at risk of imposter syndrome. For example, take the above picture of an imposter syndrome infographic it claims that BIPOC are more likely to have the syndrome, yet the study cited just showed low psychological well-being was associated with the syndrome within ethnic minorities. The study only contained Blacks and Hispanics, no comparison could even be made with whites.

Maybe all this concern about imposter syndrome is just caused by those with a political agenda grasping at straws to claim their favourite groups are oppressed in insidious ways. But with substantial affirmative action for women and ethnic minorities, I wouldn’t really be surprised if many had got into prestigious positions with a sense of being an imposter. Any intelligent black person at an Ivy League must wonder whether their admittance had something to do with their race.

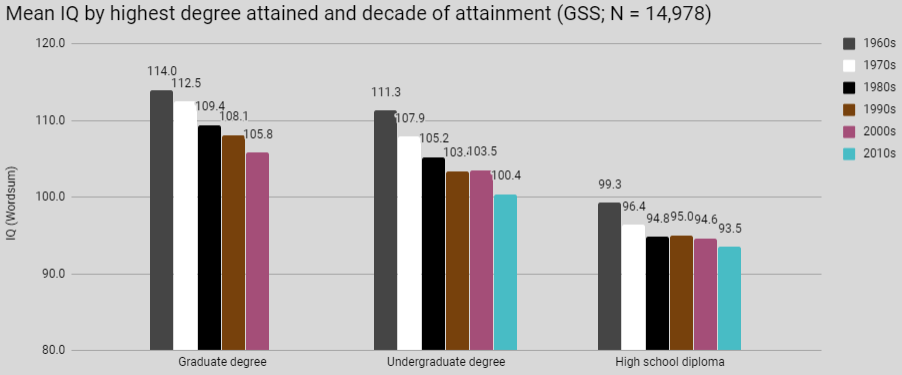

More broadly, I suspect we have fertile grounds for imposter syndrome because of the expansion of further education. As more and more people enter further education, the lower the IQ of the students. In Denmark, PhD enrollees more than doubled from 1995 to 2010 and so their IQ dropped from about 114.3 to 111.1. And the declines in the USA may have been even more precipitous. People with undergraduate degrees may have just average IQs. If anything, I wonder why there is not more talk about feeling like an imposter in the academic world. Most people at the universities really are imposters.

Sus

This wouldn't be so common if we didn't start telling every kid they're effectively a loser if they don't go to college. When I was at a university (2011 - 2015), I did have a version of imposter syndrome because I recognized, based on my math performance in middle school and high school, that I was not particularly intelligent, yet as soon as I got to college I was showered with A grades, awards, and special attention from my professors. Why? Because I could write decently well and was in journalism and political science programs alongside genuine idiots who didn't belong in any institution that's supposed to be committed to higher education.

And look, those people didn't really want to be there. They got nothing out of it. But they were told -- by teachers, by parents, by guidance counselors, and by popular culture -- that being smart is the most important thing in the world. So they faked it, and based on the sample of people I still keep up with on social media, a lot of them didn't make it. Four years pretending to care about academic subjects only to become bartenders and freelance photographers.