IQ and Interest Rates

In the summer of 2016 the German 10 year bund fell into a negative interest rate. You now have to pay the German government to lend it money! Such low interest rates are truly historic. Economists and pundits have named many short run factors such as quantitative easing (printing money to buy government debt), higher reserve requirements on banks to hold more bonds, demographic changes and ‘secular stagnation’. But the low and negative interest rates are not just unusual in the modern era, they are even stranger in the context of thousands of years of human history.

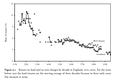

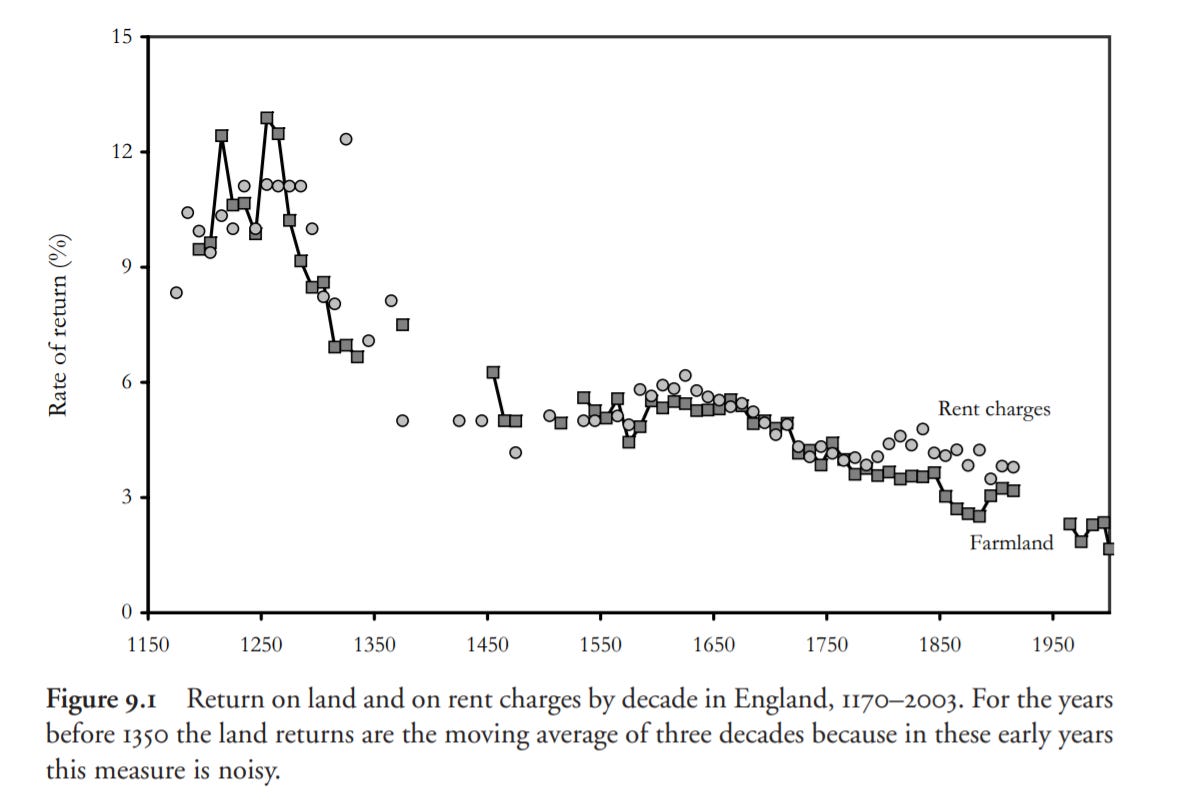

The history of interest rates has been documented by the economic historian Gregory Clark. In the ancient world, interest rates were much higher. Ancient Sumer had interest rates as high as 25%, whilst Rome often had interest rates around 10%. Since the Medieval era, interest rates have steadily fallen in England and a recent study from the Bank of England using European wide interest rates shows the same pattern, although there are a few fluctuations. See the end of the blog post for a full table of historical non-European interest rates.

The puzzle of our low interest rates is not just their current low value, but why interest rates have been falling at a constant rate for a millenia? Gregory Clark believes he has the answer. He asks us to think of interest rates as the sum of three factors:

Interest rates ≅ Time Preference (patience) + Risk premium + Economic Growth

The more patient a society is, the more willing it will be too save making interest rates fall. If the risk of investments are higher, investors need a higher return to compensate for higher risk. The higher your income growth, the higher interest you will require to make saving worth it.

Through a process of elimination Clark argues only increasing patience could have caused the fall in interest rates. Under Malthusian conditions, societies did not expect to ever get substantially richer or poorer, so growth could not have caused the decline in interest ratees. He argues that the risk premium did not fall for most of the last 1,000 years because 1. Life expectancy was constant (the risk of investment being a waste or not being paid back to your death had not changed). 2. Property Rights were secure in England for 1,000 years. 3. Political instability did not seem to coincide with higher interest rates suggesting any improvements in political institutions had not substantially altered interest rates.

But that raises the question, why did patience increase?

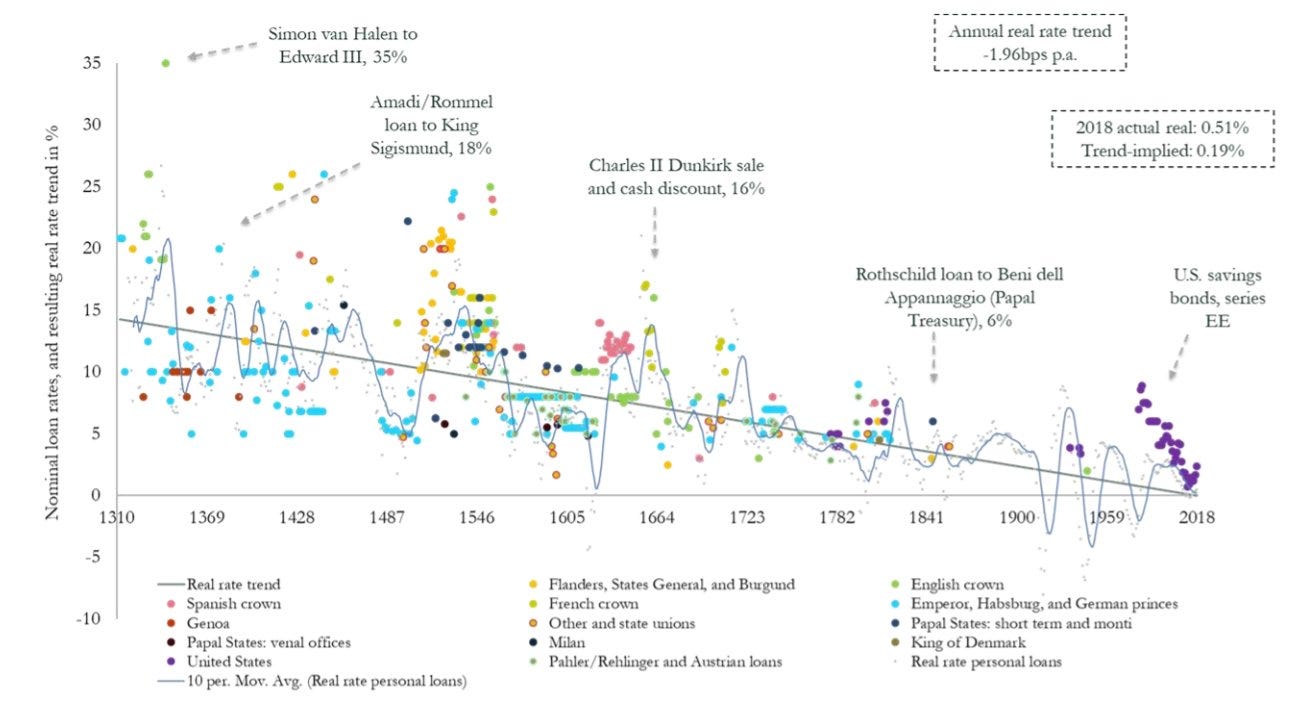

Clark explicitly argues the cause was genetic. He posits that in agrarian economies and more developed economies, with property rights and financial markets, there is the possibility and necessity of making investments. Farmers must plant seeds in spring to harvest in autumn. More generally people can invest by buying loans, buying land and investing in capital. With such conditions the most patient will become the richest, ensuring they have the resources that will maximise their reproductive success.

Wealth in wills and surviving Children in England circa 1620

The importance of accumulating wealth was very important historically in England, with richer men having more children and grandchildren. Moreover, England appeared to have a brutal class system where wealth was more important to reproduction than in other relatively developed countries. Clark makes comparisons between England and Japan and China. In China the fertility gap between the Qing aristocrats and the average Chinese was quite small compared the gap between the rich and poor in England.

Clark is hardly the first person to notice the importance of investment for reproduction. He quotes Darwin saying “Man accumulates property and bequeaths it to his children, so that the children of the rich have an advantage over the poor in the race for success.” Economist Alan Roger’s published a paper (1994) arguing that evolution was actually selecting for an interest rate of 2.5%. Why? Your child is worth half of you in terms of genetic interest. Then at the margin you are only willing to sacrifice spending on your reproduction if you can have twice the effect on your child’s reproduction. With time till first reproduction being around 25-30 years, that implies a 2.5% interest rate to double the money for the next generation. Of course don’t take the 2.5% too seriously, economics models are loose abstractions requiring the right assumptions but I think it’s a fun result.

Selection for patience is likely only part of the story though. In Farewell to Alms, Clark hints at another channel. He notes patience correlates with SAT scores, intelligence. Children, who choose to delay eating marhsmallows to have more later, grew up to smarter. A meta-analysis of 24 studies studying the relationship between IQ and patience found a 0.22 correlation. Moreover, smarter nations have higher savings rates. Given smart people tend to gain higher wealth and income, ‘survival of the richest’ probably also involved ‘survival of the smartest’. As an aside, note that although survival of the richest was harsher in England than East Asia in the Medieval era, the Chinese and Japanese are smarter today. Either English intelligence has declined faster and for longer than East Asian IQ after the Industrial Revolution (Clark does show that elite wealthy surnames in England decline in their proportion of the population after the Industrial Revolution) or East Asians used to be even smarter than English men yet still failed to start the industrial revolution.

I have not just written this blog post to summarise Gregory Clark’s theory of why interest rates have fallen. I’m also writing to critique it. Remember Clark argues patience must be the cause of falling interest rates because falling growth or reduced risk did not occur to explain the fall in interest rates. Putting aside the complex historical arguments about whether English property rights were always strong or not, the argument does not seem as water tight as Clark supposes.

For a start, that life expectancy did not change does not mean risk or uncertainty around dying had not changed. Under a Malthusian economy advances in technology just caused population to increase whilst per capita welfare and life expectancy did not. Nonetheless, technology does change your risk of dying. Imagine two societies with equal life expectancy. In one the chance of dying is random and the same for everyone. If the major threats to life are indiscriminate diseases, beasts or accidents everyone has the same level of uncertainty about their life expectancy. Nonetheless, the population is low so there is plenty of food from the land to feed the people. As such, in this society people only invest for high interest rates - there is little to gain from cultivating more land when food is plentiful but you could die tomorrow.

In another environment the people have technology - knowledge of basic medicine and improved weaponry has reduced the risk of such ‘random’ threats to life as disease and the animals. But the technology causes population to increase causing economic competition to become more intense. Individuals have less food available to them so life expectancy is the same, but now it makes sense to invest in land.

In the new environment a middle class man knows he is very likely to survive long enough to make buying more land wise, even though the poor man knows he is better off eating all his food this winter to survive. Whilst in the old environment no men wanted to invest at all.

What I’ve described above is just the ‘Life History’ theory of evolutionary biologists that harsh but stable environments encourage investment whilst plentiful but risky environments discourage investments. Between 1150 and the industrial revolution England surely experienced enough technological improvements to increase certainty about individual life expectancy even if the the average life expectancy remained constant. With rising technology and intelligence I doubt patience is the whole story.

More importantly, selection for intelligence could have reduced the risk premium of investments.

Smarter individuals might be better judges of investments, such as the quality of land, allowing them to accept a lower rate of interest. In the stock market, higher IQ investors make better stock picks and are better at timing the market and they hold more diversified portfolios. Moreover, a twin study reveals genetics accounts for one third of variation in stock market return. In other words, genetically higher IQ investors probably have lower risk.

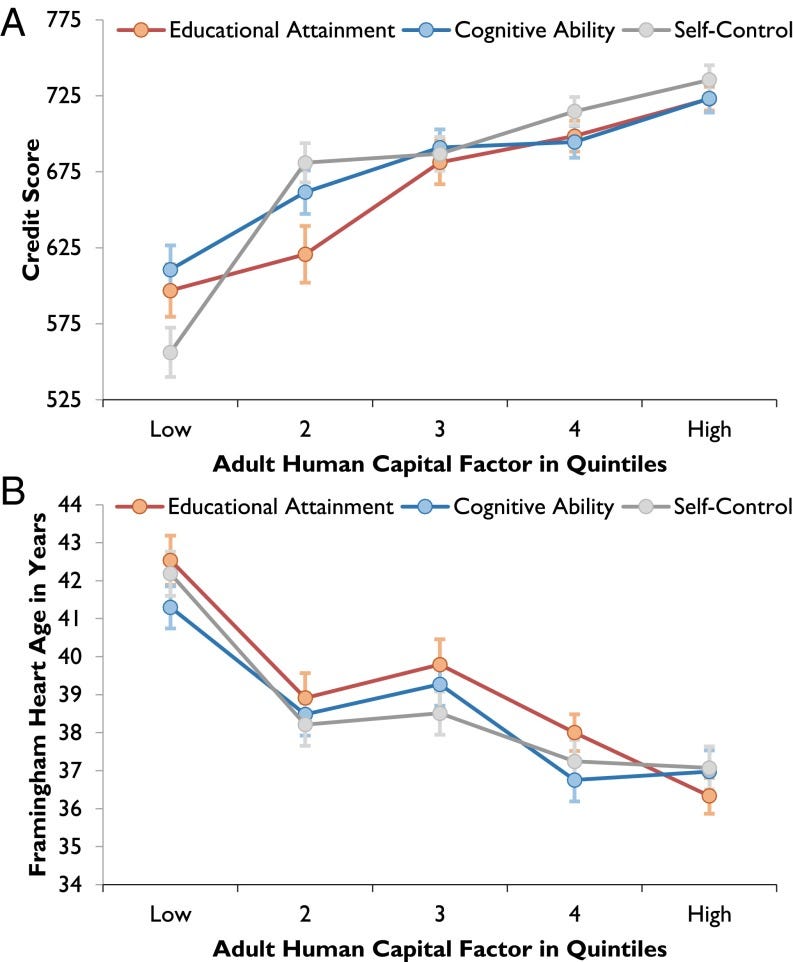

We can also study the relationship between intelligence and risk using bank loans. Companies record our financial history to create credit score the measures how risk we as clients to make loans to. As we might expect, smarter individuals have higher credit scores. Also, smarter individuals have better cardiovascular health and tend to be healthier. Again with increasing IQ and presumably healthy habits, the competition in investment for capital and land would have become more important as the factor to determining survival.

At the level of US states, average IQ correlates 0.77 with average credit score. I cannot seem to find anything on IQ and the default rate, but presuming credit scores are not biased against dumb people we can presume that smarter individuals are less likely to default. There is lot of research showing African-Americans are more likely to default and have a lower credit score than the smarter whites. Of course banks used to charge African-Americans higher interest rates because of this, so the US government made this illegal. See Sean Last’s blogpost here for a full discussion of race and interest rates.

Overall there is strong evidence to suggest smarter people make better, lower risk investments. Since economic conditions were selecting for intelligence, we should not assume patience is the entire story for why interest rates have fallen. Moreover, even though life expectancy remained the same, increasing intelligence and technology likely reduced uncertainty around death.

So what is the best explanation for how intelligence can reduce interest rates - patience or lower risk? One option is to study a cross-section of government bond yields. In this scenario patience should have a very small effect on the interest rates. First of all, in a global competitive market domestic savings only constitute a small section of the entire supply of funds available to governments and all governments are vying for money from the same global pool of investors. As such, the patience of a nation should not affect the supply side of this market. On the demand side, nations face the same market prices meaning impatient nations demanding more loans effect everyone’s interest rate the same.

A few caveats. An impatient nation that takes too many loans may become more risky. Moreover investors have a home nation bias, which may increase demand more so in patient nations. On the other hand, markets should be efficient enough to remove these price implications. If you disagree why aren’t you are busy making money exploiting market inefficiencies?

So I took data on government bond yields held by the OECD and looked at their relationship with National IQ. In December 2019 there was a negative 0.86 correlation, implying 73% of the variance in government bond yields can be explained by national IQ. Needless to say, that is a very strong relationship. This suggests that IQ has a massive effect on interest rates through risk premium, not just patience. Each IQ point is associated with a 0.26% lower interest rate.

Let's Assume that IQ affects risk the same for nations as it does for individuals. Eyeballing Clark’s data interest rates in England fell by 7% between 1150 and 1850. If all of that change was caused by IQ reducing the risk of making loans then English IQ must have increased by 23 points of IQ. I’ll be honest, that’s inconceivable. But if English IQ rose from 90 points (current Serbian intelligence) to 100, then the risk effect of IQ could explain half of the historic fall in interest rates. Note IQ is currently falling by nearly 10 points every 100 years, a 10 point gain over 700 years is not inconceivable.

Whilst Clark thought all of the fall in interest rates could be explained by patience, we have shown that falling risk, caused by higher IQ, can explain a substantial proportion of the fall. If we also consider other potential causes of falling risk, then it seems the effects of genetic patience versus genetically caused falls in risk could be of equal importance.

How do we continue research into this topic? Perhaps with more historical interest rate data and genomic estimates of historical IQ we could test how the strong the relationship really is. You might be able to borrow models from the economic literature on bond yields, then estimate the effects of National IQ on the ‘independent’ variables allowing us to breakdown the potential channels from IQ to interest rate. But this sort of fancy hierarchical modelling ought to be applied to the critical question of how IQ affects economic growth, before we consider its effect on interest rates.

Interest rates may be at historic lows, but if Clark and I are right then the current falling levels of intelligence mean interest rates will surely rise. Although this assumes the world does not experience negative growth rates, cryogenically freezing allowing people to stay patient investors, or even more crazily, the legalisation of perpetuities. When bitcoin finally stops growing, dysgenics will hold a silver lining - cheap investment.