Academia is something of a men’s club. Despite women being more than 50% of undergraduates in many disciplines, they are less likely to go into a career in academia, they achieve lower pay and lower rank within academia, their papers are less likely to be cited and they are less likely to win academic awards. Only 2% of the individuals considered to be ‘eminent’ in science, before 1950, are women. In Chemistry, 3.7% of Nobel Prize winners are women and in Physics only 1.8% of Nobel Prize winners are women.

This all begs the question, why are women performing so poorly in academia?

The ‘correct’ answer is of course that these disparities are caused by sexism or structural inequities that pull women back. Yet some research is calling this assumption into question. In hiring for tenure positions, female applicants are preferred at a 2:1 ratio over identically qualified males.

If there were structural barriers harming women, we would expect women to have to produce more than the men to compensate for the sexism against them. Yet this isn’t what we see. Upon being made professor in Sweden, female academics have fewer citations and publications. Before being hired by universities, female physicists also have fewer publications.

Emil Kirkegaard and I decided to see if these results would replicate in hiring to ‘editorial boards’. These boards are groups of (unpaid) academics who help with the administration of journals, which publish academic research. Their chief responsibility is typically to peer-review papers, advising on what should and should not be published. These positions are important, if journal editors are biased in who they pick for their board, then only a narrow group of people will get to determine what is in the scientific literature! The positions are also prestigious, help with an academic’s career and can be useful for networking.

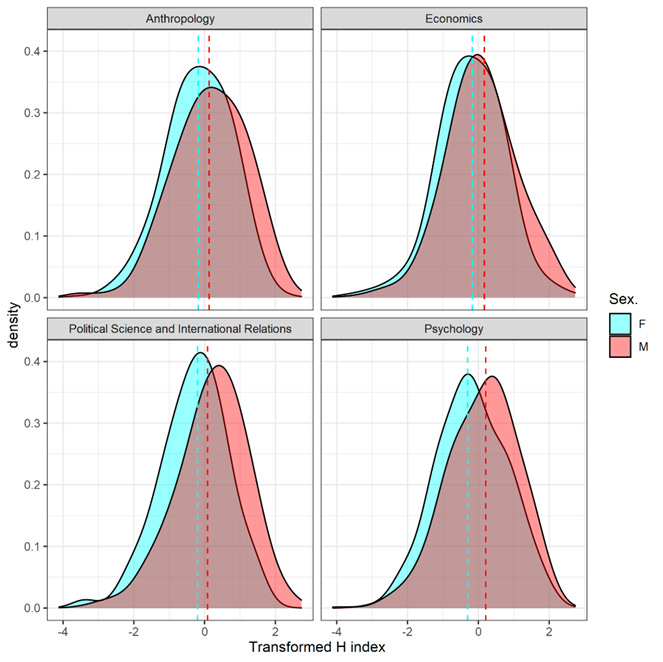

So we ran a simple test. We found 4,319 academics on the editorial boards of 120 top journals in four subjects - Psychology, Economics, Political Science and Anthropology. From Google Scholar we took the publication metrics of these scholars, chiefly their h-index. This index is a common way for comparing the productivity of different scientists, where h is the highest number of h publications you have published with h citations. Eg. If you have 5 publications with 5 citations you h-index is 5. We then did a Z-transformation of the h-index within each subject. A transformed h-index of 1 means the scholar’s h index is one standard deviation above the mean of other scholars in his discipline, within our dataset..

As expected, men have a higher research output than women in every subject. Overall, men have a 0.35 standard deviation advantage over women (p < 0.001). When we controlled for the number of years an academic has been publishing, this fell to 0.14 standard deviations (p < 0.001).

Distributions of Log10 then Z-Transformed h-Index of female and male editorial board members

Assuming the female scientists are just as capable as the men, sexism against women would mean they have to perform better than the men to compete. The evidence is *exactly* the opposite of the anti-female discrimination hypothesis. In fact, it might suggest men are being discriminated against.

Note the assumption though, maybe men, on average, are just more capable in academia? The variance of male intelligence is higher than it is for women. Amongst men, there are simply more geniuses… and more dullards. This fact implies, that at the 98th percentile of female intelligence there are three men for each woman. There’s also the fact that meta-analyses have found adult men have a slightly greater IQ on average and larger brains.

The male advantage in research output could reflect sexism against men, or men being more capable. Before we be so bold as to claim discrimination, we want to be sure. So we also ran a survey of 231 academics. We asked them 10 questions about hiring for editorial boards. The key question was “Q4. Should journal editors have a sex preference in hiring to editorial boards? (Pick 5 for no sex preference)”. Survey responders could choose a number on a scale between 0 and 10. 0 indicating that editors should prefer to hire men to their editorial boards and 10 indicating editors should prefer women.

Density plot of survey responses to “Should journal editors have a sex preference in hiring to editorial boards?” (0 represents pro-male preference, 10 pro-female preference and 5 represented no preference)

The modal response was 5, but the mean differed at 5.6 (p < 0.001). Crucially, just look at how skewed the distribution of responses is. One-third of the survey responders said editors should prefer women and only 3% said editors should prefer men. This meant for every academic preferring men, there were eleven who preferred women. I should note that 3% is tiny for a survey response. It could well be that the only people who said they preferred men made a mistake on the survey, or they were trying to troll us. 3% is, after all, lower than the 4% of Americans who believe lizardmen are ruling the earth.

It seems to be the case that academics prefer women over men. Whilst the higher performance of men on editorial boards can be somewhat explained by their greater ability, it also likely reflects the fact editors are willing to hire women at lower standards.

We should not be surprised by these results. Top publishers, such as The Lancet and Elsevier, Nature, have been demanding their editors hire more women for around the last ten years, without sufficient evidence to suppose that women were being under-hired, to begin with. Elsevier even publishes the sex ratio within editorial boards for each journal. This is to increase transparency, but it also functions to shame editors into hiring women.

With universities and academic journals eschewing quality scholars for political reasons, wise recruiters may find top talent by focusing on the ignored men.

How much could be explained by gender differences in social skills?

Minor homonym typo: "...it also likely reflects the fact editors are willing to HIGHER women at lower standards" should be "...are willing to HIRE women at lower standards."