Race, IQ and the Olympics

In my favourite episode of The Peep Show the socially hapless Mark finally makes a new friend - Darly. Of course it’s not as good as it seems when Daryl turns out to be a racist. At dinner, Mark’s black boss is discussing sports when Daryl blurts out “When are people just going to admit that you lot are better at sports and that’s just a simple fact?” Awkward.

But could Daryl the racist be right?

In the year 2021, racial differences are surely the most explosive third rail topic there can be. Nonetheless, racial differences in sports are both perhaps the most obvious and the least offensive aspect of human biodiversity. Obvious because we can see these differences simply with our eyes - for example, in general, west Africans tend to be more muscular.

We can also just look at the results of sporting competitions. Bangladesh with a population of 163 million has *never* won an Olympic medal. In every Olympics since 1984 all the finalists in the 100 metre sprint have been black - 72 out of 72, but that might change in the current games. Despite being 13% of the American population, black people make up 41% of the roster in the five major American sports leagues. In the current Swiss women’s relay team three fourths of the women are black despite black people only being 0.3% of the population.

What are the odds? That’s not rhetorical - assuming a person of each race in Switzerland is just as likely to be represented in the relay team the odds are a round 1 in 10 million. If every person in the world had an equal likelihood of being a finalist in the 100 metre sprint, the probability of 72 out of 72 finalists being black would be their proportion of the world’s population (16%) to the power of 72. The answer is 4.9732324e-58 or ‘forty-nine million seven hundred thirty-two thousand three hundred twenty-four hundred-vigintillionths’. I have not even heard of a ‘vigintillion’ before.

What are the odds that Bangladesh would receive 0 medals? The country has played 9 games, and there are 339 medal events in the Tokyo games so let’s say there are are about 1,000 medals up for grabs in each Olympic game. Let’s also again assume every person in the world has an equal chance of winning an Olympic medal whilst Bangladesh represents just over 2% of the world’s population. Then the probability of Bangladesh receiving no medals would be 1.1230626e-84 or ‘eleven million two hundred thirty thousand six hundred twenty-six ten-novemvigintillionths’.

It shouldn’t be surprising that polling from the 90s found half of Americans believed blacks made superior athletes.

It also seems to be the least offensive aspect of human biodiversity. Perhaps that’s because it’s obvious or seemingly trivial. Perhaps it’s because many races compete in one area of sport. West Africans do well in sprints, East Africans in long distance running, whites do better than blacks in swimming and asians do well in badminton and table tennis.

Although the Guardian today condemns such theories as ‘an egregiously, laughably, irresponsibly asinine line of thinking’, only 20 years ago the Guardian published an article defending and celebrating racial differences in athletic ability under the title ‘White Men Can’t Run’.

Another example of the relative recent acceptability of racial differences in sport comes from Barrack Obama. It’s said that as president he often talked about his favourite book The Sports Gene, a book which makes the point that genetic differences explain variation in sporting success - be it for individuals or races.

In popular history, there is a great celebration for the African-American runner, Jesse Owen, who won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics. His peak performance as a black man so embarrassed the racial doctrines of his Nazi hosts, Hitler refused to shake Mr Owen’s hand. In response to Owen’s success the US head coach remarked that “the Negro excels. It was not long ago that his ability to sprint and jump was a life-and-death matter to him in the jungle. His muscles are pliable, and his easy going disposition is a valuable aid to the mental and physical relaxation that a runner and jumper must have.” Although this evolutionary theory is surely too crude, it does well to explain black excellence in the Olympics Games.

Despite extraordinary racial disparities in sporting success many would have us believe that they are sociological in origin. In the critical Guardian article mentioned earlier, the author argues that whites have better job opportunities and better opportunities in pursuing expensive sports such as skiing. Africans with drive but without the same opportunity would pursue cheap sports such as running or basketball.

Of course sociological factors do play a role. India and Pakistan would not be so good at Cricket had the British not introduced the sport under the Raj. But poverty as an explanation for African success is unconvincing. Whilst lack of funding might discourage Africans from pursuing skiing it should also make them less likely to engage in sports at all.

Long distance running is just as cheap as short distance running - yet West Africans do not perform well in long distance running. This can’t be explained by socioeconomic factors, but it can partly be explained by West Africans having a lower lung capacity than East Africans. Besides, if the issue really was economic why do other deprived groups not perform as well as blacks? Bangladesh’s GDP is just as low as Kenya’s yet Kenya received 16 medals in the 2016 games whilst Bangladesh has never won any medals.

How powerful would these socioeconomic effects have to be to explain away racial differences in sport? Take again our example of how 72 out of 72 finalists in the 100 metre sprint have been black. Even if Africans were one hundred times more likely than other individuals to be a finalist, there would still only be a 2.5% chance that blacks would be so overrepresented in the 100 metres. In fact a black person would have to be 543 times more likely to be a finalist to give such a disparity even a fifty-fifty chance. Can poverty really make an African 500 times more likely to be an olympic finalist in the 100 metres?

Of course, even though the Olympic statistics make purely sociological explanations extremely unlikely, a proper hereditarian theory should explain the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ of the phenomena. Why do races differ physiologically and how do these differences affect sporting ability?

The best review of this literature has been done by Edward Dutton and Richard Lynn in their book Race and Sport: Evolution and Racial Differences in Sporting Ability. They look at studies of racial differences in physiology and then relate these differences to observed differences in sporting ability. For example, East Africans and races from high elevations tend to have a larger lung capacity. West Africans tend to have stronger quadriceps than other races, explaining their sprinting ability. Africans have a higher bone density explaining why they rarely win medals for swimming. East Asians tend to be smarter which is associated with faster reaction times which may explain their success in table tennis and badminton.

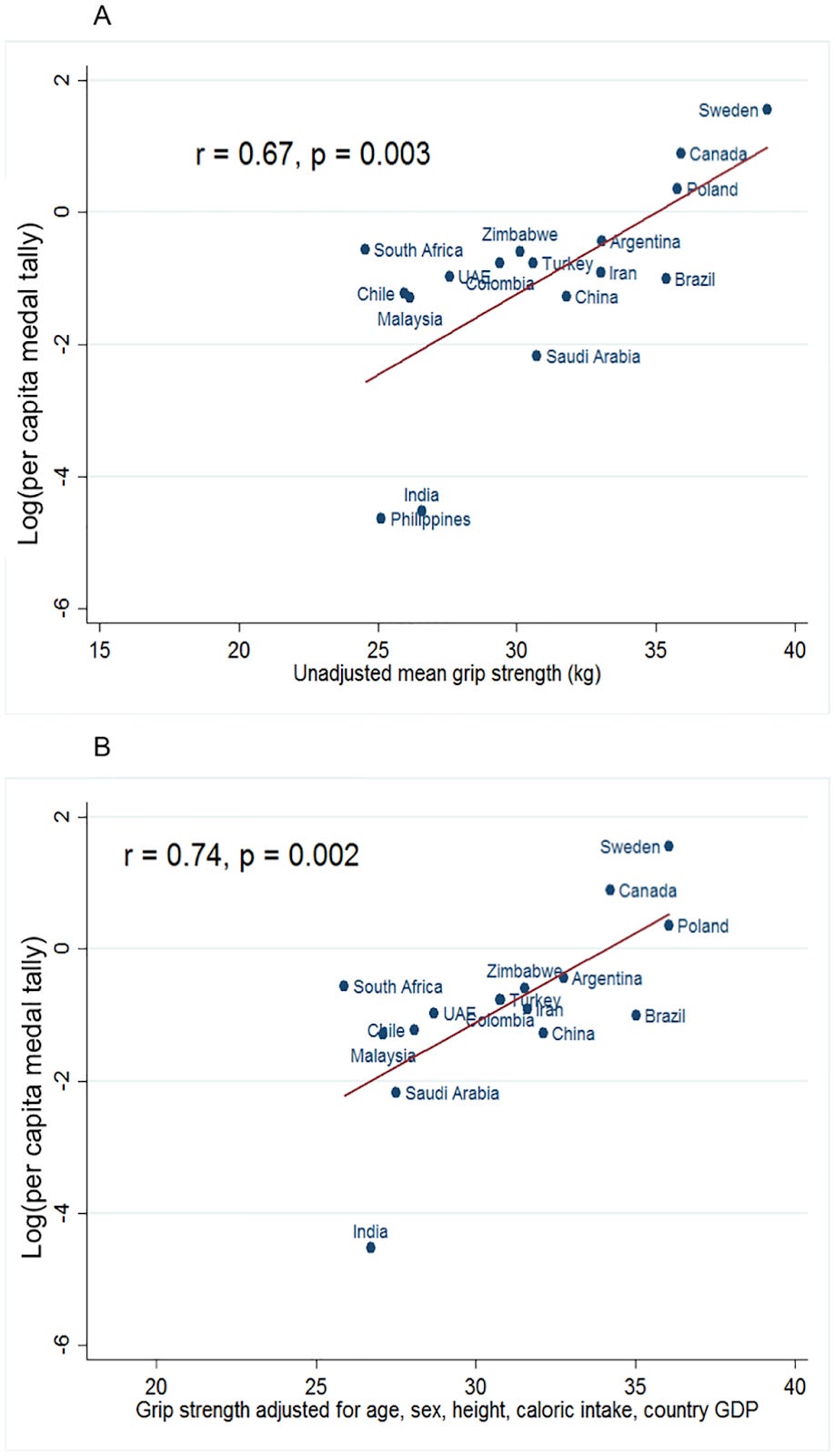

Dutton and Lynn do a great job analysing and explaining case studies of racial disparities in sports, but can we operationalise hereditarian theories to predict which nations will do best in the Olympics? A 2017 paper found that in a sample of 21 nations, average grip strength predicted more Olympic medals.

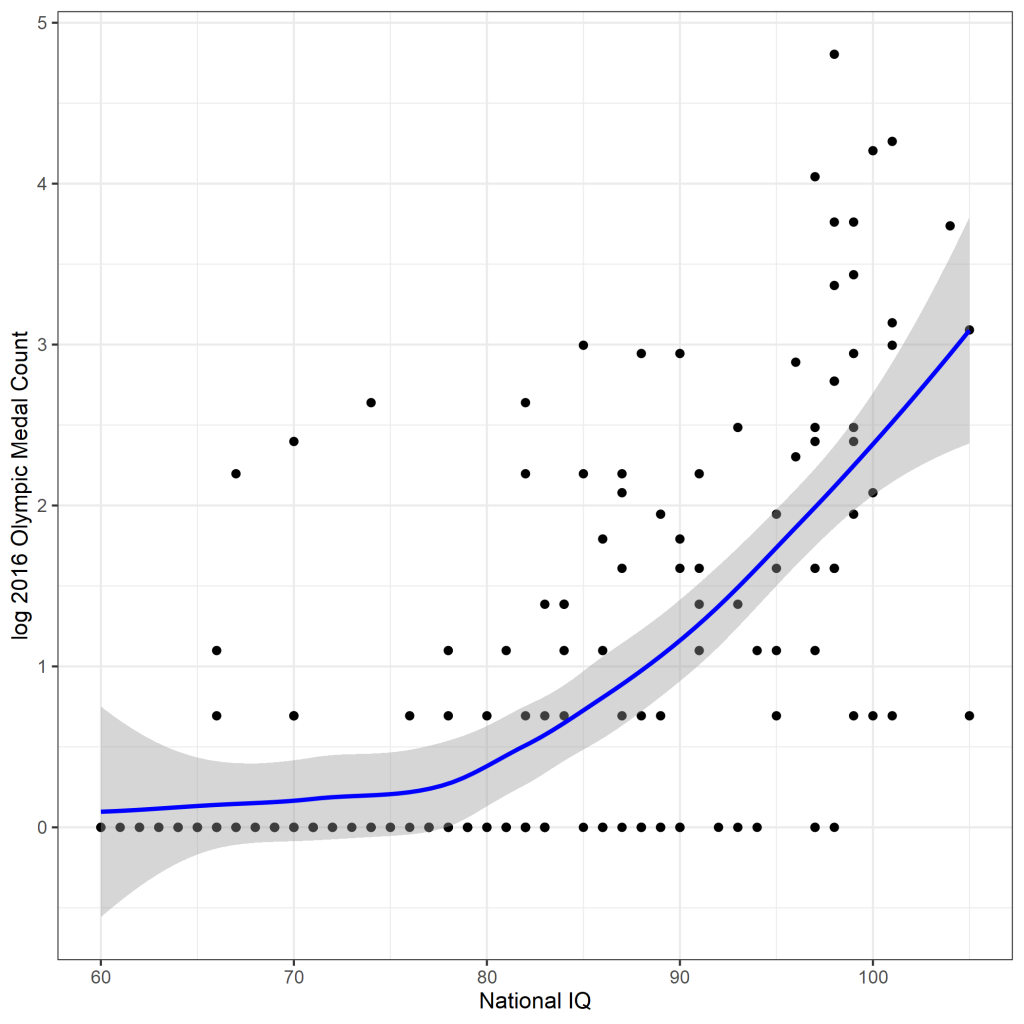

Last year I showed that more intelligent countries tend to perform better in the Olympics, whether through increased resources, smarter dieting and training or better reaction times I was not sure.

Perhaps the best modelling would be to regress Olympic Medals on a country’s ethnic proportions. You might be able to do that with the Putterman Matrix which breaks down the demographics of 160 countries by national origin. Eg. 86% of Afghanistanis’ ancestors would have been in Afghanistan in 1500, 2% would have been in Iran. You would probably try to transform national origin to race with that dataset. It might be a little tricky trying to differentiate the effect of race or national origin on Olympic medals from other regional or national fixed effects...

But all this sounds like a lot of work so let’s work with whatever data is already on my computer. I have a nice large dataset of 41 national statistics, designed for some economic research, which could help us understand the causes of Olympic success and also test some of the hereditary theories using regional dummies and national IQ.

With this dataset I employ Bayesian Model Averaging (using the bms package in R) to predict the (log) number of medals won by countries in the 2016 Olympics. The method runs thousands of different linear regression models and then takes a kind of weighted average of regression coefficients. It also calculates a ‘posterior inclusion probability’ (PIP) for each explanatory variable which tells us what proportion of models a given variable is in, but giving increased weighting to better fitting models. It can be crudely understood as the probability that a given variable is included in the ‘best’ model.

If the PIP is greater than the prior probability of a variable being employed in the true model, that suggests the data has improved our expectation that there is a real effect going on. In the results I represent the prior probability with a green dashed line.

Let’s look at which variables have a clearly higher ‘posterior inclusion probability’ than prior inclusion probability. Note - the dependent and explanatory variables, except dummies, are given in standard deviation units.

Being in Sub-Saharan Africa improves their olympic success by 0.4 standard deviations, suggesting Africans really are better at sports. As I’ve suggested, national IQ is important for Olympic success - in fact it has the third largest coefficient out of my 40 variables. A standard deviation increase in national IQ (11 points) improves a nation’s Olympic success by nearly 0.3 standard deviations - not bad! Given socioeconomic controls are employed, that suggests IQ’s importance in sports is not simply to provide funding, but rather suggest smarter people really do make better athletes.

The most influential variable is total GDP - representing a nation’s wealth and population. With more manpower and resources to use, nations do better in the Olympics.

A standard deviation increase in ‘human capital’ is associated with nearly 0.2 standard deviations more in Olympic success. This human capital index is from the Penn World Tables and is derived from the average years of schooling in a country and the returns to education in that country. Frankly, I had not expected this variable to perform so well. I guess school is where people get into sports and try different ones out.

It’s interesting that being an ex-Spanish colony reduces a nation’s Olympic success by 0.15 standard deviations. Perhaps Filipinos and Latinos simply are not very good at sports? But if that is so, why doesn’t the Latin America dummy also predict poor results in the Olympics? Perhaps it’s because ex-Portugese colony, Brazil, that has most of Latin America’s black population?