CORRECTION: Since 2010, the g-loading of GCSE has increased substantially. In 2019, the mean GCSE score correlates .72 with the score on the CAT4 intelligence test. GCSEs remain the only tests to show minimal black-white differences. Low g-loading is unlikely to explain the GCSE mystery - the case remains open. Thank you to Guy, for finding this information.

Source: https://support.gl-education.com/media/2785/cat4-international-technical-report.pdf

If a multiracial society is found where these race differences in intelligence are absent, the evolutionary and genetic theory of these differences would be falsified. - (Lynn, 2010)

Not long after the inception of IQ tests one hundred years ago, researchers noticed differences in the average scores of different races. Since then, academics have fiercely battled over the cause of these differences with environmentalists pushing for environmental causes and hereditarians arguing for genetic causes. What has never been under debate, however, is that the scores do differ and that this is caused by something… well until recently!

Writer (Chanda, 2019) has popularised the fact that in the GCSE examinations, taken by nearly all 16-year-olds in England, blacks perform around as well as whites if not better. But it was first brought to light a decade ago by John Fuerst (Kirkegaard, 2020). When pass rates for grade C or above are transformed into an IQ scale (Lynn and Fuerst, 2021), the black-white IQ gap has fallen from 9 points in 1993 to a trivial 2 points in 2018.

The GCSE statistics are astonishing. This is exactly what environmentalism could predict - as societies progress and drop racial bigotry, environmental improvements could make racial gaps trivial. So that’s it. Pack it up and go home boys, hereditarianism is over, Britain is a post-racial utopia!

What’s more, the exams seem like pretty good measures of intelligence; g (the general factor of cognitive ability) accounts for 59.3% of the variance in maths scores (Deary et al. 2007). Besides, with a sample size of over half a million each year, across multiple tests, random error from measurement has no effect on the group scores.

But there’s just one problem, the falling gap in attainment scores is entirely unique to GCSEs. Let’s look at other intelligence data available.

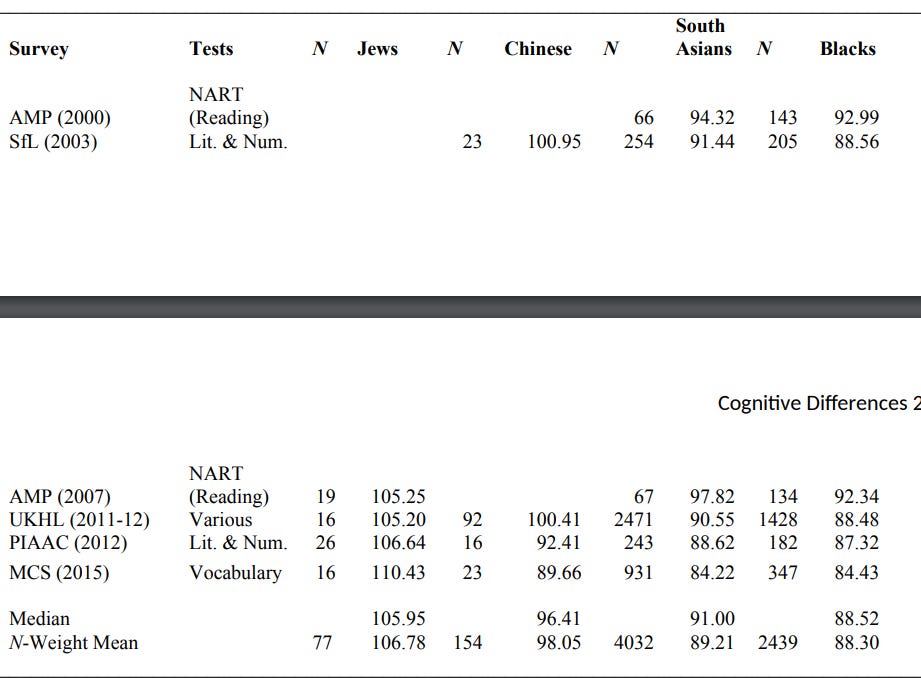

Our first port of call is (Pesta and Fuerst, 2020), summarising the results of 6 studies of UK adults. They estimate that the average Black-White IQ gap is 12.70. And the gap isn’t falling over time, if anything it's growing.

Table 1. Race-IQ Gaps from Pesta and Fuerst

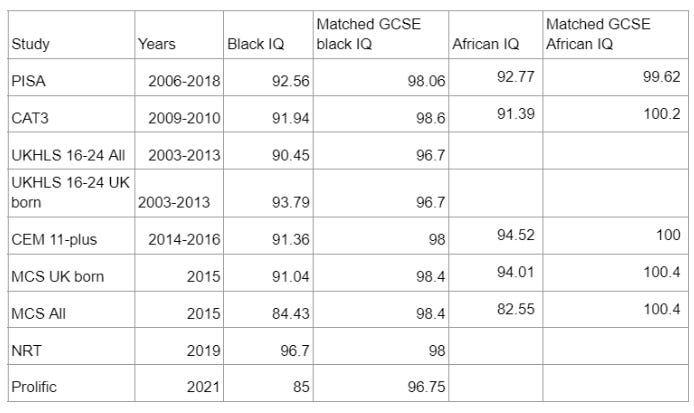

Ok then, but the GCSE gaps only closed in 2005. To make fair comparisons with the GCSE scores we need to study the intelligence of those born since 1994, people who are currently 28 or younger today. We’ve gathered all the data (we could find) on racial differences in cognitive ability within the UK for these groups and presented them in the table below. We then compare them with the IQ implied by GCSE results matched for the same birth year. A complete description of each sample is given in the appendix.

Table 2. GCSE-IQ comparison

When we look at cognitive ability tests apart from GCSEs, blacks score substantially lower than the white IQ (normed at 100). But wait, at least the National Reference Test (NRT) only finds a 3.3 IQ gap! Well, the NRT is just a GCSE-style test randomly given by the government used to set standards in exams. What’s more, contrary to the GCSE results, the Black-White IQ gap is increasing if anything, not falling. As such, the gap between what blacks score in IQ tests and GCSEs has been increasing. To make like-for-like comparisons, we should be interested in the “All” samples of the UKHLS and MCS, given that it's not only UK-born students who take the GCSEs, but we have included the UK-born subsamples out of interest.

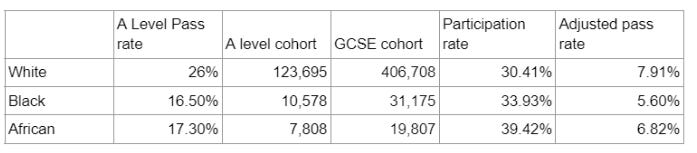

It’s not just IQ tests that disagree with the GCSEs, the results from other educational tests show significant black-white gaps. Let’s look at A-levels, the most common test given to 18-year-olds in England.

The standard A-level metric the government releases is the % of a group achieving 3 or more As at A level (Gov, 2022). As we can see in table 3 we have returned to the expected results: Blacks and Black Africans perform worse than Whites.

But wait, there is a problem: a greater percentage of Blacks attempt the A levels than Whites do (GCSE cohort matched to the 2019 test takers (Gov, 2020)). What if less intelligent Whites are less likely to attempt A-levels, pushing up the pass rate? Well, to deal with this, we can use the adjusted pass rate. This is essentially the percentage of the entire White/Black population which achieves As. We have here introduced the opposite bias as before: if more Blacks attempt the A levels, a greater percentage of them will pass. This has the effect of artificially compressing the racial gap, nevertheless, we can still see that Whites outperform both Blacks in general and African Blacks specifically.

Table 3. A level pass rates by Race

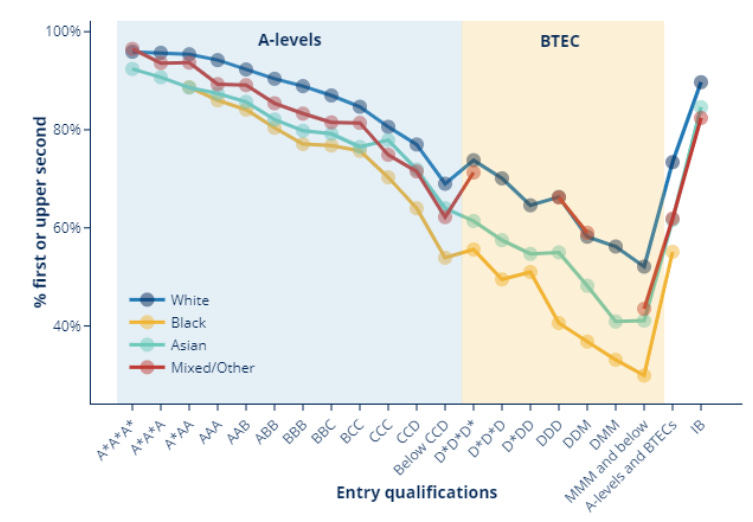

At the university level, Blacks perform much worse than Whites, there is a 6% gap in the dropout rate and a 12% gap in the rate at which students obtain a first or upper second (the highest two qualifications in the UK) (Roberts and Bolton, 2020).

We do however have two biases in the data: Blacks are more likely to go to university (bias increasing racial gaps) and are less likely to go to “high tariff” (the best) universities (bias shrinking racial gaps). Unfortunately, the gap between White and Black students in enrollment is too large for our A-level adjustment trick to work (Whites would need to have at least a 100% upper second+ rate to match the adjusted Black rate).

Instead let’s hold A-level results constant and see how our students do, since A-level results favour Whites, this will introduce a bias against finding racial gaps. We can see (OFS, 2021) that for every single A-level grade, Whites will go on to outperform Blacks at university. For the stats nerds amongst you, this is a lovely demonstration of Kelley’s Paradox.

Whatever measure of cognitive ability we look at we find black-white gaps. The GCSEs are a bizarre outlier. The environmentalist who uses the GCSE results in their argument must explain how equalising the environment could extinguish racial differences in one test at the age of 16, but somehow not affect any other test. And besides, do environmentalists really want to claim that the UK is an egalitarian post-racial utopia?

But the GCSE mystery is still a problem for hereditarians. If blacks really are genotypically less intelligent than whites, why do they perform so well in this school exam?

Peter Frost (2021, 2019) has proposed some explanations (in the comments he suggests we have mischaracterised his views). His first explanation is that blacks are likely to cheat more. He cites evidence suggesting this is the case in Nigeria and in British universities. His second argument is that because of selection through we have a sample of especially intelligent blacks. (Lynn and Fuerst, 2021) also point out that 7% of the British population don’t take GCSEs, instead taking iGCSEs, these people are disproportionately white students in high-performing private schools.

We don’t wish to deny these claims. They are probably correct - the black-white IQ gaps shown in our tables are generally less than the approximate 15-point gap seen in America. Whilst these arguments suggest British blacks should perform better than Africans on IQ tests - they can’t solve the GCSE mystery, and they cannot explain why blacks score so well only in GCSEs.

So what is actually going on with the GCSEs? Well dear reader, like any good mystery writer we gave you some clues but left out key pieces of information till the end. Firstly, Deary et al. (2007) conducted an analysis of the g-loading of GCSEs on a 2002 dataset, before the black-white GCSE gap started to close. We have no reason to suppose that GCSEs are still such good measures of intelligence, which leads us to the second withheld piece of information.

Between 2005 and 2010 GCSEs underwent a series of reforms to help “disadvantaged” students (Townsend, 2003; Wikipedia 2022) becoming more modular and focusing on coursework.

During this period the rate of grade inflation skyrocketed: from 2000 to 2004 the percentage of students achieving 5 or more A*-C increased by a total of 2.6%, with the largest 1 year grade inflation of 1.1% (2004). Then from 2004 to 2005 the rate of grade inflation hit 2% in a single year; from 2004 to 2008 the total grade inflation was a full 6.5%! (Guardian, 2013)

If we look specifically at maths. According to a government review from 2004-2008 (Gov, 2010)

The major change that affected all GCSE mathematics examinations between 2004 and 2008 was a move from a three-tier examination system of foundation, intermediate and higher tiers to a two-tier system, comprising foundation and higher only. These changes had a significant effect on the demand of the examination by changing the balance of questions focused on each grade.

The spread of grades to be covered in each tier increased and in some awarding organisations this resulted in a rise of structuring within questions.

In addition, question design showed an increasing trend towards structuring of questions. Both factors made examinations less demanding over time. The increasing numbers of centres entering students for specifications with modular examinations highlighted a mixed effect on demand.

OCR’s modular assessment design minimised the effect of the changes and allowed standards to be maintained over time, whereas AQA’s modular design (also available in 2004) fragmented the assessment and increased structuring in questions, making the examinations less demanding.

The 2006 GCSE mathematics subject criteria, also introduced a significant change in the balance of questions focused on each grade; in each tier, 50 per cent of the weighting had to be focused on the lowest two grades and 25 to 30 per cent focused on the top two grades. The purpose of this change was to make sure that all students have an opportunity to show what they know, understand and can do.

In 2004 only one awarding organisation (OCR) had a modular GCSE as its leading specification, by 2008 there were three: AQA, CCEA and OCR. Modular specifications offer an opportunity to re-sit each non-terminal module once.

By 2008 the maths GCSEs were unrecognisable from those tested by Deary et al. (2007): The intermediate tier was removed and exams were made shorter. 1 mark questions, a previous rarity, exploded.

For GCSE English language: from 2002-2005 exam times were cut, OCR introduced modularity, annotations were banned in books and the syllabus was changed in 2004 (Gov, 2007).

What appears to have happened is quite simple: GCSEs lost their validity as intelligence tests during these reforms. Not only did GCSEs become easier but less related to intelligence. As we know from Spearman’s hypothesis, the less an intelligence test is g-loaded (the less it measures intelligence) the smaller the racial gaps (Rushton and Jensen, 2005). [1]

We saw this phenomenon previously at Anglo Reaction when we studied how the civil service had explicitly chosen to reduce the g-loading of their recruitment tests in order to hire more minorities. The Civil Service’s newer test halved the black-white gap.

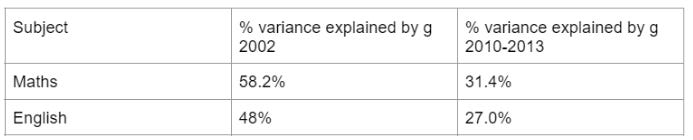

This is not just conjecture, we have data from the Twin Early Development Study (TEDS) to investigate this (Rimfeld et al., 2015). Children from this study took their GCSEs between 2010 and 2013. Let’s compare TEDS to our Deary et al.’s results from the 2002 GCSE. We have two directly comparable GCSE measures: Maths (the most g-loaded GCSE in both samples) and English. The result has been a complete collapse in the g-loading of GCSEs over the period.

Table 4. g-loading of GCSEs

58% of the variance in maths GCSE results was explained by intelligence in 2002, yet by 2010-2013 this halved to 31.4%. By comparison, 73.4% of the variance in SATs in America could be explained by g before the 1994 reforms (Frey and Detterman, 2004). GCSEs are just not a good measure of intelligence anymore.

As the reforms would suggest, the GCSEs have also become more trainable. The shared environment accounts for 14–21% of the variance in GCSE scores compared to only 5% for intelligence (Rimfield et al., 2015).

Conclusion

We have here presented our solution to the GCSE mystery. The answer? GCSEs are no longer a good measure of intelligence. The culprit, as is so often the case in Britain: Blair. The evidence: countless other datasets contradicting the GCSEs’ no race gaps result and the fact race gaps were reduced at the same time as GCSE quality was undermined - exactly as Spearman’s Hypothesis would suggest.

But we are good scientists here and we make our theories falsifiable hypotheses. Environmentalists can falsify our theory with the following evidence.

Showing that GCSEs are actually still highly g-loaded. This is actually possible: the Gove reforms starting in 2013 reversed the trend of modularity and replaced coursework with controlled assessment, although 1-mark questions remain pervasive in GCSE maths, and the intermediate tier is still nonexistent. There aren’t any studies on the GCSE g-loading post-2013 as far as I’m aware.

find another g-loaded test from a UK sample showing no Black White intelligence gaps to confirm the GCSE results. We look forward to being proven wrong.

[1] Because we don’t have individual subject level data, only 5+ GCSE pass rates or 5+ including English and maths, (pending a freedom of information request Simon Wright is making) it is impossible to tell if certain subjects saw race gaps fall before others.

Bibliography

Chanda, 2019. Why Do Blacks Outperform Whites in UK Schools? [WWW Document]. Unz Rev. URL https://www.unz.com/article/reply-to-lance-welton-why-do-blacks-outperform-whites-in-uk-schools/ (accessed 10.21.22).

Deary, I.J., Strand, S., Smith, P., Fernandes, C., 2007. Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence 35, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.02.001

Frey, M.C., Detterman, D.K., 2004. Scholastic Assessment or g?: The Relationship Between the Scholastic Assessment Test and General Cognitive Ability. Psychol. Sci. 15, 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00687.x

Frost, P., 2021. Evo and Proud: Nigerians, Scrabble, and the GCSE. Evo Proud. URL https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2021/03/nigerians-scrabble-and-gcse.html (accessed 10.21.22).

Frost, P., 2019. Evo and Proud: Not what you think. Evo Proud. URL https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2019/12/not-what-you-think.html (accessed 10.21.22).

Gov, 2022. Students getting 3 A grades or better at A level - GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures [WWW Document]. URL https://web.archive.org/web/20220830133020/https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/a-levels-apprenticeships-further-education/students-aged-16-to-18-achieving-3-a-grades-or-better-at-a-level/latest (accessed 10.18.22).

Gov, 2020. GCSE results (‘Attainment 8’) - GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures [WWW Document]. URL https://web.archive.org/web/20201220003749/https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/11-to-16-years-old/gcse-results-attainment-8-for-children-aged-14-to-16-key-stage-4/latest (accessed 10.18.22).

Gov, 2010. Review of Standards in GCSE Mathematics 33.

Gov, 2007. Review of standards in GCSE English 2002–5.

Guardian, 2013. How have GCSE pass rates changed over the exams’ 25 year history?

Jerrim, J., 2021. PISA 2018 in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales: Is the data really representative of all four corners of the UK? Rev. Educ. 9, e3270. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3270

Kirkegaard, 2020. Chanda Chisala did not come up with the UK race gaps argument. Clear Lang. Clear Mind. URL https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2020/09/chanda-chisala-did-not-come-up-with-the-uk-race-gaps-argument/ (accessed 10.21.22).

Kirkegaard, E.O.W., 2022. The Intelligence Gap between Black and White Survey Workers on the Prolific Platform. Mank. Q. 63, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.2022.63.1.3

Lynn, R., 2010. Consistency of race differences in intelligence over millennia: A comment on Wicherts, Borsboom and Dolan. Personal. Individ. Differ. 48, 100–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.09.007

Lynn, R., Fuerst, J., 2021. Recent Studies of Ethnic Differences in the Cognitive Ability of Adolescents in the United Kingdom. Mank. Q. 61, 987–999. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.2021.61.4.11

OFS, O. for students, 2021. How do student outcomes vary by ethnicity? - Office for Students [WWW Document]. URL https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/differences-in-student-outcomes/ethnicity/ (accessed 10.18.22).

Pesta, B.J., Fuerst, J., 2020. Measured Cognitive Differences among UK adults of Different Ethnic Backgrounds: Results from National Samples (preprint). PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3txk4

Pokropek, A., Marks, G.N., Borgonovi, F., 2022. How much do students’ scores in PISA reflect general intelligence and how much do they reflect specific abilities? J. Educ. Psychol. 114, 1121–1135. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000687

Rimfeld, K., Kovas, Y., Dale, P.S., Plomin, R., 2015. Pleiotropy across academic subjects at the end of compulsory education. Sci. Rep. 5, 11713. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11713

Roberts, N., Bolton, P., 2020. Educational outcomes of Black pupils and students 8.

Rushton, J.P., Jensen, A.R., 2005. Thirty Years of Research on Race Differences in Cognitive Ability. Psychol. Public Policy Law 11, 235–294.

Townsend, M., 2003. GCSE reform planned to save teenage “lost souls.” The Guardian.

Wikipedia, 2022. General Certificate of Secondary Education. Wikipedia.

Appendix to Table 2:

First up we have the Millenium Cohort study (Pesta and Fuerst, 2020) which, as the name suggests, is exclusively a study of people who were born in 2000-2001 so took their GCSEs in 2016.

Next the UKHLS gives us a subsample of people aged 16-24. Since data was gathered between 2011 and 2013 this means GCSEs were taken between 2003 and 2013, mostly capturing the post-racial era.

(Lynn and Fuerst, 2021) give us a compilation of several studies of adolescents in the UK, conducted between 2006 and 2019. First we are given the results of our national reference testing (NRT) conducted in 2019. This is essentially a longitudinal version of the GCSEs so any flaws with them should also carry over to NRTs. Then we have PISA results, an internationally standardised test of maths, English and science that is highly g-loaded (Pokropek et al., 2022). (Jerrim, 2021) even suggests that in the 2018 dataset poorly performing students are underrepresented, which will have the effect of compressing any racial gaps.

CEM 11-plus gives us a sample of Buckinghamshire children who attempt to get into grammar schools. It is a test measuring verbal, quantitative, and non-verbal abilities. This is the least representative sample of the group, but is included as supportive evidence for our other datasets.

CAT3 is probably the best study in the review, conducted in 2010 on 11-12 year olds, well after the racial gaps had vanished in 16 year olds, and with a huge sample size (200,000). In fact it is the same test used to validate GCSEs as good IQ measures by (Deary et al., 2007).

Study 1c of (Kirkegaard, 2022) gives us a sample of survey workers for the prolific platform (a rival to Amazon’s MTurk) using a Visual Paper Folding IQ test. The sample size is very young (mean 24.31, max age 39) and as far as I can tell was conducted in 2021. This means that the oldest person in the sample will have taken their GCSEs in 1999 and the average one in 2013. Again, this is not a representative sample, although MTurk workers appear to have similar IQs to the general population.

I have built a table of all the datasets, matched (as best as possible) to the average IQ estimated from GCSEs taken by the same age cohort (Lynn and Fuerst, 2021). The IQs are all normalised so that White pupils have an IQ of 100. Matching was done to the same birth year, so for example children took the CAT3 exam in 2010 and were 11 years old, this matches to 2015, for datasets taken over multiple years (or multiple ages) we take the average GCSE gap. This matching process makes very little difference though, since IQ gaps are very similar from 2005 onwards.

"Hereditarian, (Frost, 2021, 2019) has proposed some explanations. His first explanation is that blacks are likely to cheat more."

I fell off my chair when I read that sentence. Did I actually write that? Well, no. I wrote that Nigeria is a low-trust society and that Nigerian students feel it is legitimate to cheat on university exams. It doesn't follow that they are more willing than white Europeans to cheat friends and family members. (I suspect the reverse is true). It's an even greater semantic leap to say that "blacks" in general are likely to cheat more.

"His second argument is that because blacks faced immigration restrictions in coming to the UK, we have a selected sample of especially intelligent blacks."

I considered that argument and rejected it. I did make a second argument, i.e., higher cognitive ability does exist among some African groups, like the Igbo. Why didn't you mention it?

"Nigerian academic achievement may be genuine in some cases. This is particularly so with respect to the Igbo, who have a longstanding record of achievement within and outside school."

Finally, I have never identified myself as a "hereditarian." The term is meaningless and is most often used by people who want to shut down the nature-nurture debate (like "ultra-Darwinian" and "genetic determinist"). Why are you using it? Please don't use me as a sock puppet for views I don't actually hold.

"58% of the variance in maths GCSE results was explained by intelligence in 2002, yet by 2010-2013 this halved to 31.4%. By comparison, 73.4% of the variance in SATs in America could be explained by g before the 1994 reforms (Frey and Detterman, 2004). GCSEs are just not a good measure of intelligence anymore."

I believe you should use the g-loading rather than the variance explained by g, as the expected gap would be closer to proportional to g-loading than to variance explained by g? I.e. a g gap of 1 standard deviation would not lead to a test gap of 0.58 and 0.31 standard deviations, but instead closer to 0.76 and 0.56 standard deviations? (Not exactly these numbers because Cohen's d is kind of weird, but approximately.)